I do not consider myself as a circuitist and I cannot boast of being an expert of Augusto Graziani’s thinking. However, while writing this post I realized that the extent of his direct and indirect influence on my work has been probably greater than I previously thought.

I was lucky to have the chance to “discover” Graziani in the early stage of my education as an economist. The first time I was presented with his theory of the monetary circuit I had just finished my bachelor degree, when the professor who introduced me to (and made me fall in love with) economics, Marco Missaglia, recommended reading Graziani’s 1996 Teoria del circuito monetario. This suggestion was meant to help me understanding the concept of monetary theory of production. I had bumped into that concept while reading about endogenous money supply, which, in my very limited understanding of the economics debate at the time, was an astonishing theory (I believed it was a way to repel the “Say Law”). Notwithstanding this, what exactly a monetary theory of production meant remained, for me, at best unclear. I found Graziani’s work crystal clear and even simple at first. The sense of simplicity soon vanished during my PhD when in 2010 Marco Veronese Passarella’s lecture on the monetary circuit revealed some of the theoretical sophistication underneath Graziani’s circuit, such as money as a form of capital or the role of the interest rates and profit. Even recently, thanks to a lecture by Riccardo Bellofiore hosted by the Italian Post Keynesian Network, I could appreciate how what may appear as a simple representation of the functioning of a monetary economy is the results of a refined reasoning on different crucial issues in the theoretical debate: the roles of power relationships and that of financing, the nature of money, but also crisis theory, and thus the monetary essence of a capitalist system.

Indeed, the clarity of Graziani’s version of the monetary circuit appears to me not as resulting from simplicity, whereas from the capacity to identify and communicate the very core of the matter at stake determined by substantial theoretical awareness.

In a sense, the seek for clarity was what led Alberto Botta, Daniele Tori, and myself to try to analyze the securitizing system through the lens of the monetary circuit (Botta et. al 2015). The paper’s primary goal was not to “update” the monetary circuit by taking-into account the evolution of the financial system, but to use it to shed light on the role of securitization in the monetary and financial system, following the flux-and-reflux of money. To make sense at the aggregate level of the role and impacts of securitization, we applied to the financial system the idea that “[a] complete theoretical analysis has to explain the whole itinerary followed by money, starting with the moment credit is granted, going through the circulation of money in the market, and reaching the final repayment of the initial bank loan” (Graziani, The Monetary Theory of Production, 2003, p.26).

This, together with the idea that “the starting point for a construction of a macroeconomic model can only be the identification of the social groups present in the community” (ibidem, p. 19) allowed us to disentangle the balance sheet interconnections between the real and financial side of the economy, and, most importantly, within the former. On top of that, we underlined how the evolution of the financial system determined the opening of two new circuits. The first one opens when banks issue loans to the household sector and closes when financial intermediaries, which collect household saving issuing shares, purchase loans to securities. The second, opens with the direct financing of financial intermediaries by commercial banks.

Some of the conclusions of the paper are admittedly non completely loyal to the circuit proposed by Graziani. Passarella (2022) stresses how our interpretation of household credit as initial finance is in contrast with the original analysis by Graziani, which, as underlined by Bellofiore (2019), made explicit that household credit ought to be conceived as indirect credit to firms (Graziani, 2003, p.21).

Nonetheless, our rather `unconventional’ view was that only reversing the perspective and putting the financial system at the center of the stage, looking at the influx of money there as the starting point, it is possible to develop an understanding of its functioning. In Graziani, household saving could take the form of securities and equities, issued by firms, or deposits, the latter was diverted from becoming financial finance resulting in new debt for firms. We tried to show that the securities issued by the financial system, transforming household mortgages into mortgage-backed securities, have their specificities, in terms of money creation and destruction, and exert distinct impacts on the economic system, with respect to income inequality and instability above all.

The results of that paper paved the ground for ensuing works (e.g. Botta et. al 2021, 2022, and 2024) in which, with Alberto Botta and Alberto Russo, we modeled the impacts of securitization on inequality and financial (in)stability through Agent-Based Stock-Flow Consistent (AB-SFC) modelling. Referring to a previous intervention by Marc Lavoie on this blog, the passage from the monetary circuit to SFC modelling felt rather “natural”. Indeed, in both approaches one of the key questions is “where money comes from and where does it go?”. This is central for Graziani, as exemplified by the first of the two above quotations, and it is exactly the question which led Morris A. Copeland to develop the flow of funds database which has been foundational for SFC models. The monetary circuit and the SFC modelling approach developed by Wynne Godley have undoubtedly many differences, but they share the same focus, putting the monetary nature of the economy at the very centre of the stage, one from a theoretical and the other from a modeling perspective. If one uses the theoretical lens of the monetary circuit, in a sense s/he is led to apply a SFC approach when it comes to modelling.

Lately, once again with Alberto Botta and Daniele Tori, we resumed our investigation on the financial system observed through the lens of the monetary circuit, in a paper presented at the conference in memory of Graziani after 10 years from his death held at the Università del Sannio last May. First, we map the sequential steps of money creation, flows, and destruction, inside the financial system, focusing mainly on securitization, repos, and “originate to distribute” practices. We then use elements of Graziani’s theoretical approach to analyze the implications of the emerging monetary relationships.

We begin identifying a “radical coherence” between these financial practices and capitalism as they feed channels of profit realization, mainly credit to households and residential investment. Indeed, the surge in mortgages in the run-up to the 2007-2008 crisis partially represents consumption credit in the form of “home equity extraction”.

Second, we believe that the different degrees of access to credit according to social groups, which is one of the tenets of Graziani’s theory, is relevant even within the analysis of the financial system. Different kinds of financial entities (i.e., sectors within the financial systems) embody diverse access to financial markets’ resources in relation to social groups. In particular, hedge funds (HF) are used by a small portion of households (HH), say rentiers. These financial institutions benefit from a preferential access to credit, thanks to their strong linkages, as prime brokerage and even affiliation, with investment banks, which in turn have easy access to credit through their often-institutionalised connection with commercial banks. This allows HF to have highly leveraged balance sheets, therefore enabling rentiers investing in them to magnify their financial income. Workers’ gates of access to the financial markets (i.e. other kinds of funds) do not provide the same ease of access to credit, they act as more standard financial intermediaries, as they can only invest existing savings.

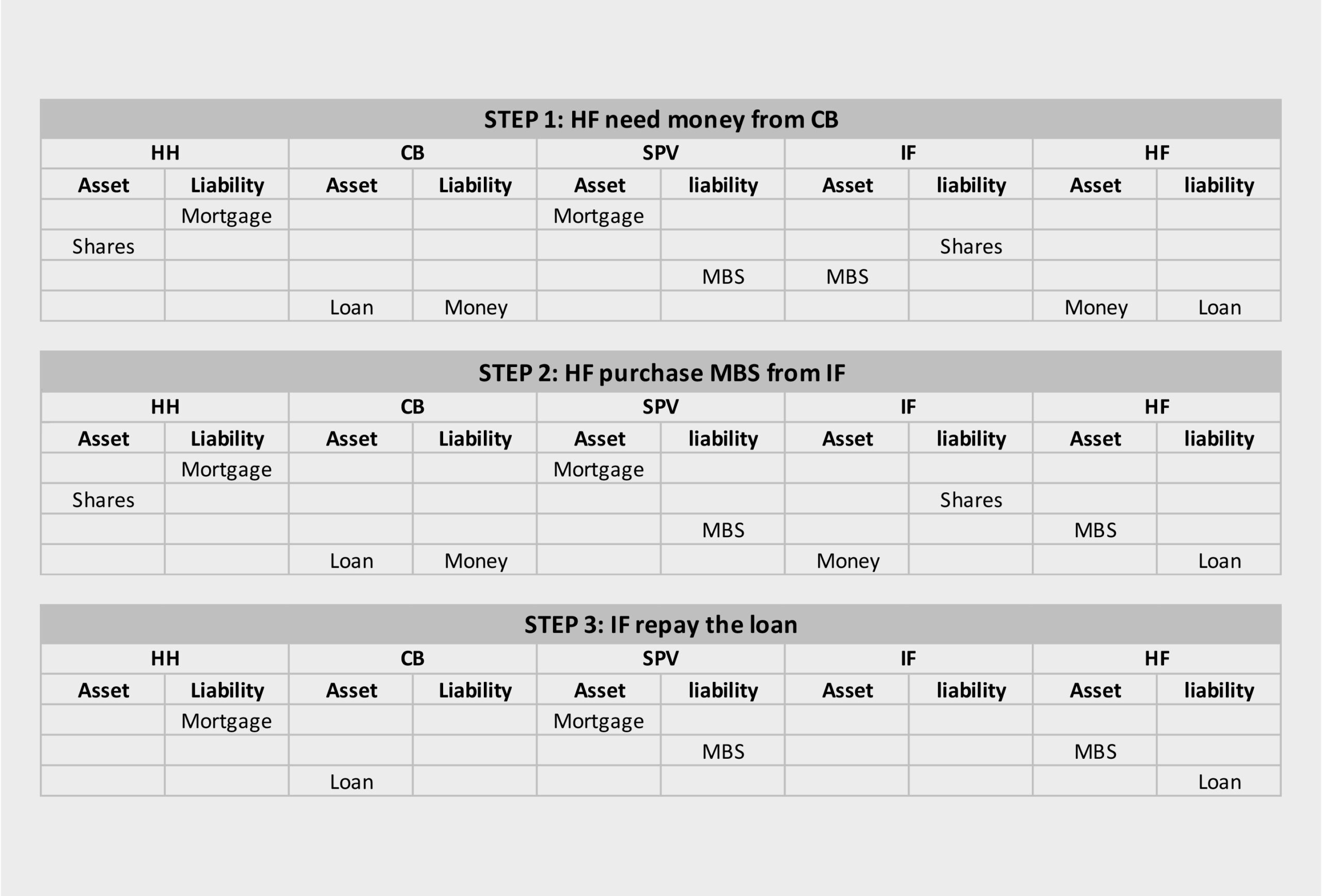

The third consideration rests on a balance sheet representation of the securitizing system. What emerges is that securitization – the process of converting assets into tradable securities – determines an immediate destruction of money but a complex intertwinement of debt relations may emerge. A portion of the money created issuing the mortgage, equal to the asset securitized, is immediately destroyed. The money used by special purpose vehicles (SPV) to purchase mortgages and then by investment funds (IF) to purchase mortgages backed securities need nonetheless to come from somewhere. According to the kind of liability issued to collect that money, different balance sheet relations will ensue (see an example in the figure below at the end). The financial system can issue/produce an increasing amount of financial assets starting from the creation of a given amount of money. This determines a more acute systemic financial instability as during financial turmoil all institutions with a pending liability need money to settle their positions. As in the musical chairs game for kids, while the music plays the number of kids (financial assets) dancing around a single chair (bank deposits) can increase with no harms. When the music stops the chair is not able to accommodate everyone.

Related to this, a final consideration can be drawn from Graziani’s distinction between a credit economy and a monetary economy. In the latter, money is a form of debt resulting from triangular relation, it is in the ‘nature of credit’, but not a direct credit between two agents, thus reflecting an immediate and final payment. We believe that, thank to repos and rehypothecations, non-bank financial institutions are indeed able to significantly increase the velocity of circulation of money within the sector and to expand their balance sheets. Indeed, around 50% of non-bank financial institutions’ assets consist of either receivables from (i.e. credit towards) other investment banks or repos (usually in favor of other investment banks). In this sense, in normal times, liquidity may never be an issue. Nonetheless, these institutions are not able to issue assets with the features listed by Graziani and they cannot determine an immediate and final payment, which when needed requires commercial bank deposits. As suggested also by Jo Michell in his article for this blog the, the relationship with commercial banks is still central, also for financial firms.

Let me finish by explaining how, while I know that Augusto Graziani’s work has been inspirational for my research, I am probably still not fully aware of the impact that it had on my work. In fact, most of this impact has probably been indirect as my learning of post-Keynesian economics is largely rooted in Marc Lavoie’s works, and Riccardo Bellofiore was the supervisor of my PhD thesis. Nonetheless, two years ago when I started lecturing “Economia Monetaria e Creditizia” at the University of Insubria, I immediately knew that I was going to devote some lectures to the theory of the monetary circuit of Graziani. Hopefully his work will be inspirational also for the future generations of students there.