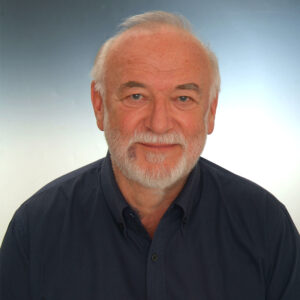

I met Augusto Graziani for the first time in the early 1980s. He was then already a highly renowned economic theorist, particularly famous for his contributions to monetary economic theory, whilst I was a freshly appointed professor of economics at the University of Bremen. Graziani was a most pleasant and indeed exceedingly agreeable man and a highly impressive scholar. What immediately impressed me were his sparkling eyes. They expressed curiosity, open mindedness and profundity. Knowing him a little better, one could not escape admiring him for his immense erudition, sharpness and brilliant intellect. And despite all these remarkable features, there is one feature that stuck out: his remarkable modesty. According to my experience there are only a few scholars of his intellectual calibre in our profession that compare with him in this regard. Talking to him, reminds me today of the characterisation of David Ricardo put forward by the novelist Maria Edgeworth: “”I never argued or discussed a question with any person who argues more fairly or less for victory and more for truth. He gives full weight to every argument brought against him, and seems not to be on any side of the question for one instant longer than the conviction of his mind on that side. It seems quite indifferent to him whether you find the truth, or whether he finds it, provided it be found.”

There are two instances, in particular, which I recall with great joy. I had written a paper about Piero Sraffa’s criticism of Hayek’s monetary theory of the business cycle, Hayek’s response and Sraffa’s rejoinder. I was very surprised and of course extremely pleased when Graziani asked my permission to translate the paper into Italian and publish it in Studi economici. This was a great honour to me and I accepted with deep gratitude.

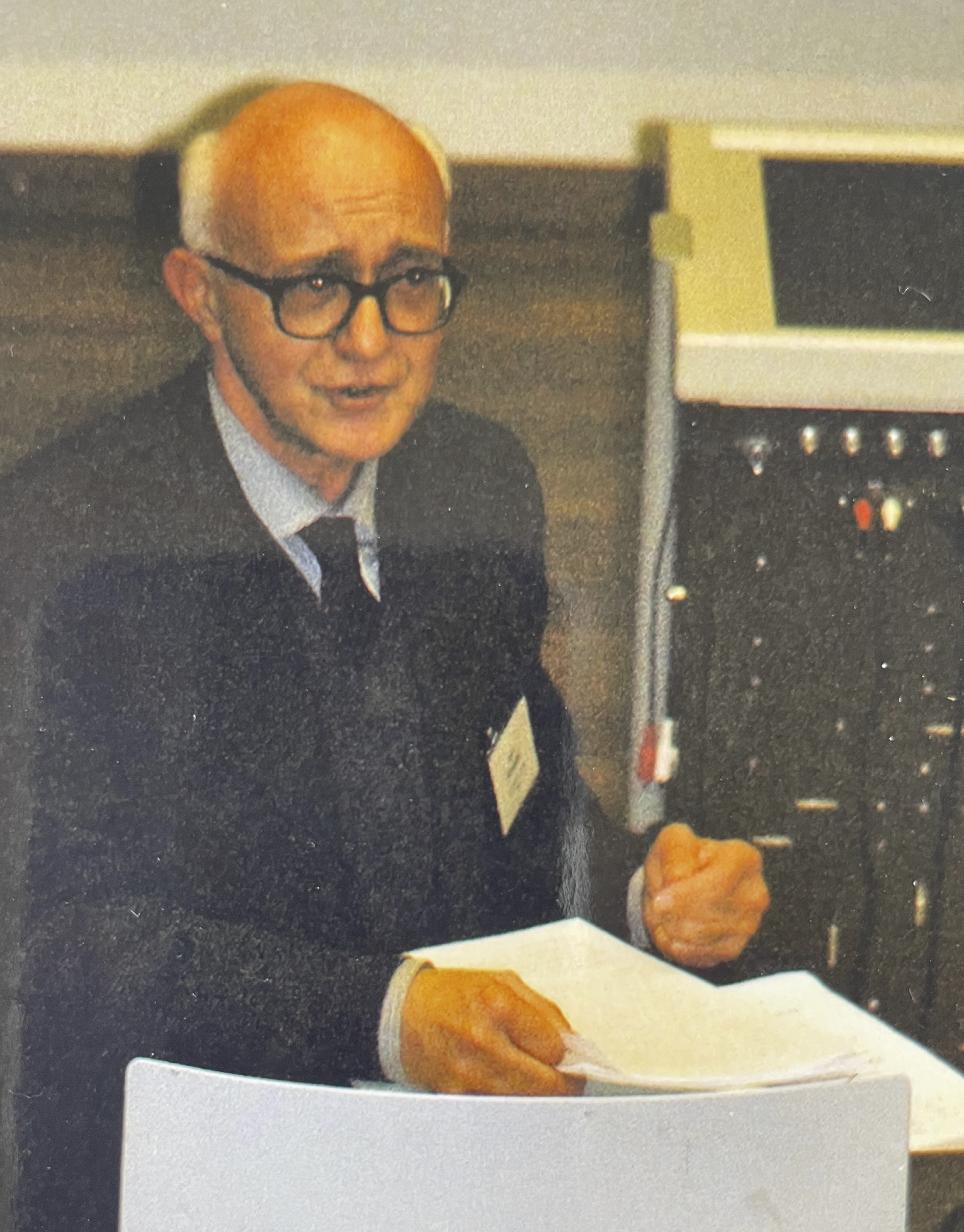

When in the year 2000 we organised the annual conference of the European Society for the History of Economic Thought at my University in Graz, the formation of a new government in Austria, which included the right wing party FPÖ, caused a considerable turmoil. I received mails from several colleagues, who cancelled their participation because they felt that Austria was no longer a secure country. Graziani, while understandably on the alert, did not share this sentiment. He came to Graz, gave an excellent talk, participated in discussions and stood up on behalf of liberty, freedom and democracy. (See the snapshots taken at the conference.)

He was a remarkable man, a remarkably good man.